What Does California’s Power Grid Need to Handle the Coming Wave of Electric Vehicles?

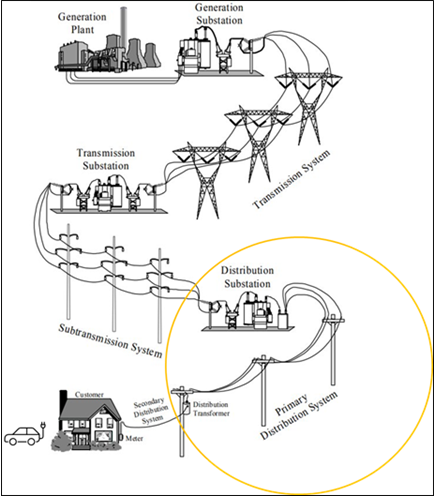

Source: Richard E. Brown, Electric Power Distribution Reliability, 2017 (Brown) at 4.

1. If people plug in their cars at the right time, it could halve the necessary distribution infrastructure and its associated costs.

A recent California Public Utilities Commission study conducted by Kevala (“Kevala Study”), a private energy modeling company, estimated the cost to upgrade California’s distribution grid to be about $50 billion. Our team at the Public Advocates Office conducted its own assessment, published this month, which estimated the cost to be almost half of Kevala’s estimate, roughly $26 billion through 2035.

The stark contrast in these costs predominantly comes down to different assumptions as to when electric vehicles will charge. This cost differentiation also serves as a pointed reminder regarding the future of electrification in California: we must pursue the most cost-effective ways to electrify the grid, and getting it wrong could cost ratepayers tens of billions of dollars in the long run. These studies show that it is critical to pursue electrification thoughtfully and help inform policymakers of the different pathways that lie ahead and what mechanisms need to be considered in order to keep costs as low as possible.

2. If done right, electric vehicle charging will put “downward pressure” on rates.

Neither our study nor the Kevala study claims to perfectly forecast the future. But what we do know – by comparing the two studies – is that the time at which electric vehicles charge will have a significant impact on the cost to upgrade California’s distribution grids to serve electric vehicles and other electrifying loads. Our study follows the assumptions of the California Energy Commission that electric vehicles will avoid charging in the evening, when demand on the grid is already at its highest. This would reduce the strain that electric vehicle charging places on the grid.

Our study also found that electrification may help reduce electric rates (the price paid by consumers for each unit of electricity they use). This is important because the price of electricity will be increasingly compared to the price of gasoline and other energy sources when consumers make purchasing decisions. For example, electricity costs for charging are rising closer to parity with gasoline as seen in the graph below.

Source: Q2 2023 Electric Rates Report (ca.gov)

Another way to state this is that electrification will apply “downward pressure” to electric rates because the increase in electric rates to pay for grid investments is more than offset by the larger amount of electricity sold. More units of electricity being sold means that the fixed costs of all grid infrastructure can be spread across more units of electricity, and thus, electricity can be sold at a lower price. Think of it like a high-volume fast-food restaurant. The more hamburgers that McDonalds sells, the lower the price it can offer because fixed costs like rent are spread across more hamburger sales.

To be clear, this does not mean that we predict falling electric rates in the future—other costs, such as climate change mitigation or decarbonizing electricity supply can still cause rates to increase.

Many things need to go right for this downward pressure to be realized; there is a potential for upward pressure instead if infrastructure is overbuilt relative to actual future load. Therefore, it is paramount that planning be flexible, adaptable, and incremental so that investment plans can be adjusted if load does not appear when and where it is forecasted to appear.

3. Distribution grid upgrades are being built at the right pace.

Finally, we also found that the current pace that utilities are upgrading their distribution grids is near to that of our electrification model. This means that we think that distribution grid infrastructure will not be a bottleneck for people electrifying homes and vehicles. If you’d like to read more about these findings and details on our methods – including how we used 31 million vehicle registration records provided by the Department of Motor Vehicles – you can read our published report.